“Would you sell me that sofa?” Mustafa, our Moroccan “tout” asks. Blair explains our house and all its

furnishings are rented, not for sale. . We

don’t usually invite itinerant salesmen into the house: it is just too cold on the porch to look at

the socks and belts and towels in his pack.

We buy a plaid wool cap. I ask

him to sell my artwork. “People will

think I stole it,” he says.

We are constantly interrupted by traveling salesmen: earlier in the week, Innocent (from Nigeria)

stopped by and sold us two waffle-weave towels.

Selling is the only work new immigrants can do, without getting into

trouble. Fortunately, there isn’t a

police category dedicated to controlling these poor, hard-working

renegades. We give them oranges and

glasses of water and pay too much for everything.

Blessing asks us for a ride up to the Borgo from the Conad

super market, where he sells rather good-looking blouses and slacks, small

carpets and socks (we have actually bought lots of clothes there, sometimes

with American guests). He has all the “dirt”

on Stimigliano, and the skinny on other immigrants. Frank, who always wants us to adopt him, has

moved to Poggio Mirteto; Blessing says, “Frank got a job there”. “People around here lie,” he tells us, explaining how, in fact,

the new building under construction isn’t going to be a clinic, but rather an

old folks’ home. We commensurate on how

good, and inexpensive, the food in Italy is, and housing; we all have health

care. “It’s easy to live, but it’s

almost impossible to work here. If I

could go to the US or Canada I’d never look back”, he lets us know.

I always say I would never had made it in Italy without the

immigrants. They punctuate my life with

surprises. 20 Italian men sitting in the

piazza won’t as much lift a finger as I struggle with two large grocery bags

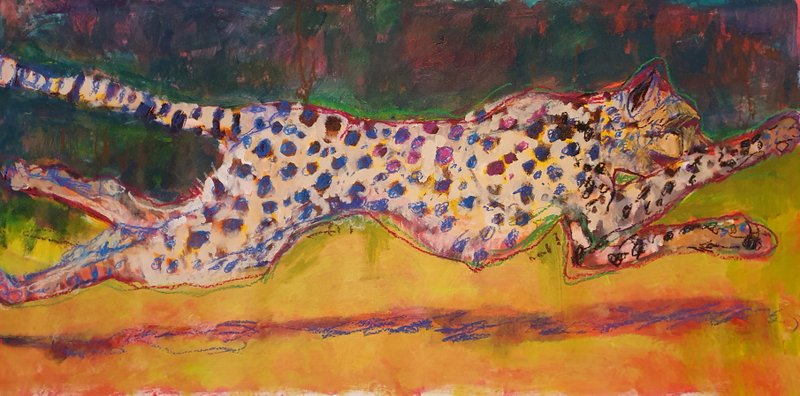

and a dog; the Africans will help. An itinerant salesman will stop by the studio

and tell me how good my painting is. It’s

that interruption that sometimes keeps me going.